Sacramento Northern Essentials

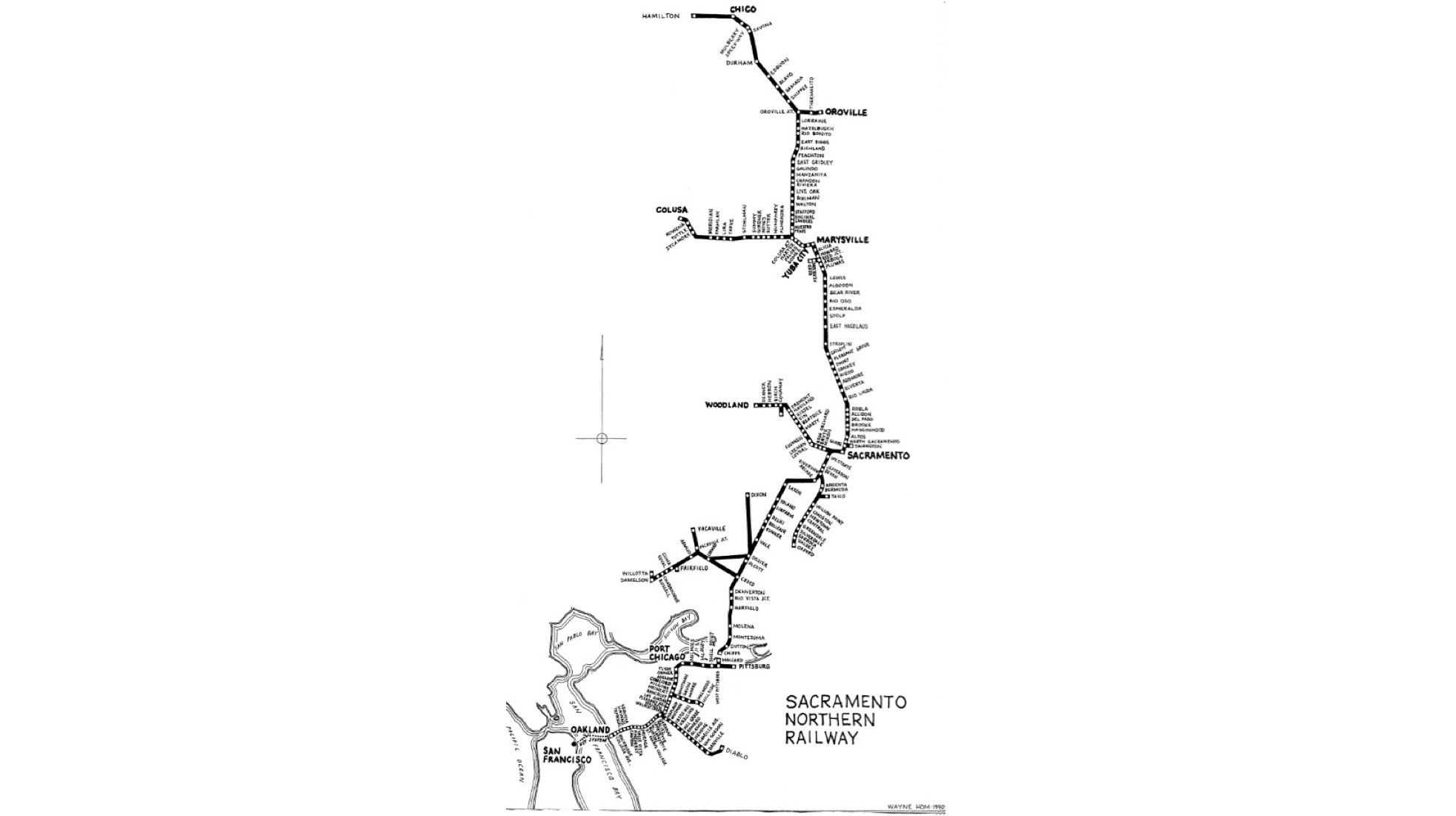

A composite map labelled Sacramento Northern Railway reveals nothing about time or succession, and lacks some essential details. However, a very useful tool in which to uncover hidden treasures related to important historical events in Northern California history and beyond. But first as background, electricity and hydroelectric power, all told in “P.G. and E. of California, The Centennial Story ... 1852-1952” by Charles M. Coleman.

L187-05-Wayne Hom Drawing, Courtesy John Harder, (Image 1 of 19)

The 19th century ended with the fleeting achievement in 1895 of the Livermores with the Folsom Powerhouse on the American River and its transmission of 11,000 volts for 22 miles to Sacramento. In 1901, backed by Romulus Riggs Colgate of the renown family, John Martin and Eugene J. de Sabla, Jr.’s Colgate Powerhouse on the Yuba River, shown here, bested the Folsom mark.

L187-10-Courtesy Yuba County Library, YCL 019, (Image 2 of 19)

In 1901, the Colgate Powerhouse delivered 40,000 volts over 142 miles to Oakland, the longest ever achieved. Here a south view, Vallejo to Crockett, of the crossing of Carquinez Strait 50 years later on June 8, 1953, the 4427 feet gap also a record for its time. Martin and de Sabla’s success accelerated the consolidation of competing electric companies, forming the California Gas and Electric Co. in 1901, and eventually the Pacific Gas and Electric Co. in 1905.

L187-15-Copyright California Department of Transportation, 3298-16 , (Image 3 of 19)

Martin and de Sabla acquired the North Pacific Coast Railroad in 1902, and converted a portion of the steam-based, narrow-gauge section in Marin County to a third rail-based, standard-gauge electric line, the North Shore Railroad. To do so, a 150-mile transmission line from a subsidiary power company was established to the power house they constructed at Alto, here seen in a south view with Northwestern Pacific car nos. 378, 381 and 255 on Sept. 9, 1940.

L187-20-Roy Covert Photo, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 20152nwp, (Image 4 of 19)

The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 provided an opportunity for the Great Western Power Co. to compete with Pacific Gas and Electric. Based initially at Big Bend on the Feather River, Great Western was derived primarily from the Western Power Co. owned by E. T. and Guy C. Earl with significant New York-based financial backing. Here, an undated view of a Great Western Power Co. plant as seen from Hanlon Shipyards at the foot of 5th St. in Oakland.

L187-25-Louis L. Stein Collection, Courtesy Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library, (Image 5 of 19)

On the surface, the formation of the Sacramento Northern Railway was a financially necessary consolidation of north end and south end railways by the Western Pacific, WP, as 1929 unfolded. The two competing electric companies would merge one year later. On page 216 of his book, Coleman reveals that de Sabla, but not Martin, had rebuked the Earl brothers’ offer of Western Power Co. soon after the latter was formed. Who knows how history would have been changed if de Sabla had been open to an offer.

L187-30-Courtesy Stuart Swiedler, (Image 6 of 19)

The Northern Electric Co., NE, began by constructing a 25 mile line through sparsely populated farm land from Chico to Oroville, opening to the public on April 25, 1906. The route’s big challenge is shown here, the crossing of the Feather and adjacent land that was subject to flooding and the intensive gold dredging efforts of the Natomas Cons. Co. Service was extended between Marysville and Chico on December 6, 1906.

L187-35-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 108539sn, (Image 7 of 19)

The devastating flood of 1907, shown here in a west view down Montgomery St. at Myers St. in Oroville, damaged much of the NE. The Panic of 1907 added to the financial ruin of NE primary financial investor and visionary force, Henry Butters. Reorganization of the company as the Northern Electric Railway Co. later that year followed, with Louis Sloss and Ernest Lilienthal taking over corporate control of the NE as it looked to expand to the Bay Area.

L187-40-Courtesy the Meriam Library, California State University, Chico, sc20254 , (Image 8 of 19)

The extension of the NE south of Marysville was heavily influenced by Martin and de Sabla, who favored the more efficient third rail they had utilized in Marin County over the overhead wire initially used on the NE. This north view circa 1910 just south of Tres Vias shows progression of this transition. The exposed third rail proved to be a safety issue for the NE, although overhead wire was retained in the busy urban centers and many additional stations.

L187-45-NE Photo, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 108567sn , (Image 9 of 19)

The NE continued to lose money, and by Oct. 1914 it was placed in receivership to Pacific Gas and Electric attorney John P. Coghlan. It took four years for the railway to rebound somewhat financially, and it was reorganized as the Sacramento Northern Railroad, SNRR, on July 1, 1918. All ties to the former executives and board were severed, and George Detrick was made president with his main objective to shop the line to the WP. This undated image confirms the reorganization.

L187-50-Randolph Brandt Photo, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 110139sn, (Image 10 of 19)

Although WP took over control of the SNRR or north end late in 1921, the deal was not finalized until 1925 due to ICC regulatory demands. The acquisition was legally made to a separate entity, the Sacramento Northern Railway Co., that was created by the WP in mid-1921. Shown here in a north view, a two-car SN train composed of SN 129 and SN 226 wait for a parent WP freight to clear the crossing at Globe in North Sacramento on Oct. 6, 1940.

L187-55-Louis Bradas, Jr., Photo, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archive, 68464sn, (Image 11 of 19)

Concerning the WP’s acquisition of the Sacramento Northern Railroad, this map from 1926 shows WP’s sphere of influence in Northern California including the SNRR and the Tidewater Southern.

L187-60-Poole Bros. Chicago, Moreau Collection, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 12 of 19)

As Harre Demoro notes in “Sacramento Northern’, page 24, Henry Butters had envisioned the NE to eventually connect Chico to Vacaville via Colusa and Woodland, and continue to Vallejo, San Rafael, and Tiburon, with a ferry connection to San Francisco. The focus was passenger service. Interestingly, Butters lived in Piedmont, and the WP’s solution for the NE was Butters’ back yard and with no emphasis on passenger service.

L187-65-Poole Bros. Chicago, Moreau Collection, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 13 of 19)

The solution for the north end was the south end, or as it was called in the 1920s, the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad Co., SF-SRR. Unlike the NE, the previous iteration, the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern, OAE, had ended up at auction in 1920 at Martinez, only to be reacquired by the same group that had run it aground. The SF-SRR had developed a close working relationship with the SNRR, all in line to encourage acquisition by the WP.

L187-70-Poole Bros. Chicago, Moreau Collection, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 14 of 19)

The original plan for the OAE in 1909 was that of a modest interurban, the Oakland and Antioch, OA, that would connect the growing industrial center of Bay Point through farm land to Concord, Walnut Creek, and Lafayette, with a branch line to the north approach of Mount Diablo. At that point, the actual path to Oakland and San Francisco was being debated. Shown here is a northeast view of an Oakland and Antioch train at the Santa Fe Bay Point terminal.

L187-75-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 34273sn, (Image 15 of 19)

By March of 1911, the railway was reorganized by adding “and Eastern” to its name and issued additional stock, and, as noted by Ira Swett in “Sacramento Northern”, page 110, “Eastern” at first meant extension to Stockton, a plan quickly changed to Sacramento. Later that year they proceeded with what the other railroads had avoided; construction of a 3200 ft. tunnel between Contra Costa and Alameda Counties that also required creation of a cut, as seen in this east view circa 1911, to enter Shepherd Canyon in Oakland.

L187-80-Cook and Cooke Photo, Sappers Collection, Courtesy BAERA, WRM, 24110sn, (Image 16 of 19)

The WP acquired the SF-SRR at the end of 1928 through the Sacramento Northern Railway Co. entity that had been used to acquire the north end. The negotiations and regulatory review had lasted 6 years. The WP invested more heavily in the SF-SRR portion by extending freight service to the US Steel Columbia plant in Pittsburg, creating the Holland Branch, and connecting the Vacaville Branch to the mainline through Creed. Still, the passenger service was formidable relative to 2019.

L187-85-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 17 of 19)

Sadly, this extraordinary railway did not last very long, with freight-only isolated islands surviving into the 1970s as seen in the right panel. In 2019, only three sections of original right-of-way are used; east of McAvoy Rd. to access the spur for ITW Angleboard by the Union Pacific RR; from West Sacramento, including the Port, to Woodland by the Sierra Northern RR and the Sacramento RiverTrain; and 5 of the 22 miles in Solano County preserved by the Western Railway Museum.

L187-90-Wayne Hom Drawing, Courtesy John Harder, and Moreau Coll., Courtesy BAERA, WRM Archives, (Image 18 of 19)

Unlike what has been presented in this review, the hidden treasures are events that are under-represented or neglected in books or for which images are lacking that provide the connection of the SN to the history of Northern California. To facilitate this process, the SN map will be flipped counterclockwise to better fit the viewing template. Next time, the first topic in this series, the Chestnut St. Connector.

L187-95-Wayne Hom Drawing, Courtesy John Harder, (Image 19 of 19)