Part V – Clyde and the Mystique of the Riveter

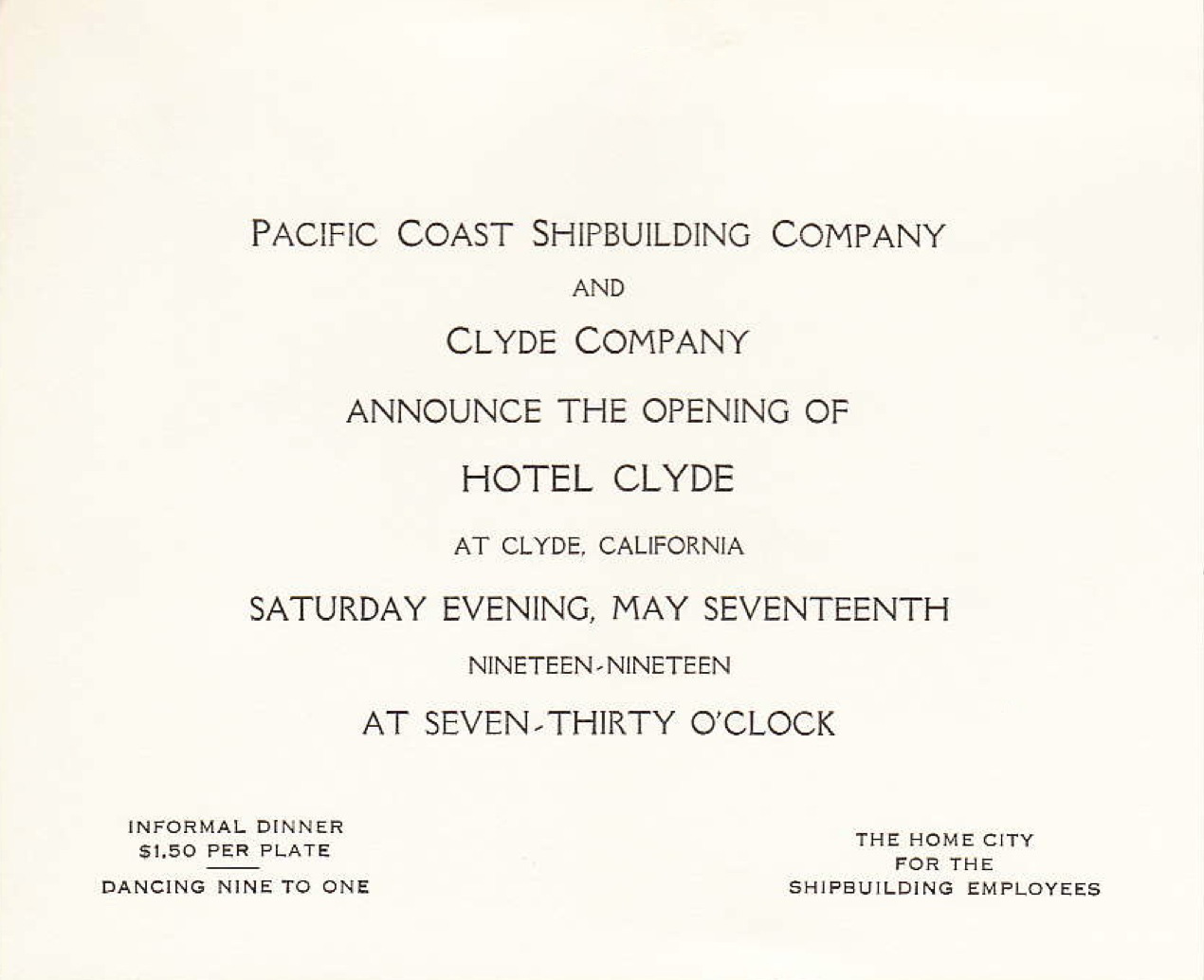

Your invitation to the opening of the Clyde Hotel, May 17, 1919. Clyde refers to the river of that name in Scotland, known primarily for its shipbuilding history. Very appropriately named so by entrepreneur Robert Noble Burgess, connecting his ancestral roots and his investment into the shipbuilding business.

L150-05-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38561, (Image 1 of 21)

Two individuals of note on Robert Noble Burgess’ invitation list were the Mitchells. Now that Clyde was created and the Pacific Coast Shipbuilding Company had been in operation for a year, the final piece was establishing fast, dependable transportation connecting the shipyard to its workers. For Burgess, that was the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern.

L150-10-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38561, (Image 2 of 21)

The town of Bay Point would have been the more logical place to create housing for the shipyard workers, but Burgess had held the land of the former Government Ranch for a decade without a return of his investment. The June 30, 1918 Oakland Tribune announced his intentions to create Clyde, naming Livermore banker and financier, L. M. MacDonald, as the President of the Clyde Company. Ref: G4364 C56 1919 C5 Sheet 1

L150-15-Courtesy Earth Sciences and Map Library, University California, Berkeley, (Image 3 of 21)

Using government loans obtained through the creation of the shipyard, building the town and hotel was completed in less than one year, this undated imperfect west view panorama circa 1918-1919. MacDonald enlisted noted architect Bernard Maybeck to consult on the design of the hotel and homestead plots provided by architects E. W. Cannon and G. A Applegarth.

L150-20-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 96352cv, 96358cv, 96359cv, (Image 4 of 21)

Tracking the numbers and places of residence of the Pacific Coast Shipbuilding Co. workers became a preoccupation of all the parties involved in worker transport once the shipyard was in full operation in mid-1918. In this correspondence, Harry Mitchell of the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern appears conditionally willing to consider transport of the workers “to the gates of the plant.”

L150-25-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38562, (Image 5 of 21)

The SN also depended on Melville Dozier, Jr. to keep his eye on employee movement as he designed and constructed the rail overpass of the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe mainlines. Here is an excerpt from a letter to Harry Mitchell from June 13, 1918.

L150-30-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38562, (Image 6 of 21)

Burgess was unable to convince any of the four railroads to bring trains directly to the shipyard using his newly constructed overpass. Harry Mitchell of the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern did agree to service that would transport workers to Bay Point from as far as Diablo. At its inception, the cost of a monthly ticket from Diablo was raised to 14.65 dollars, but a 12-ride discount was also introduced.

L150-35-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38561, (Image 7 of 21)

While gazing on the left portion of the west view panorama circa 1918-1919 from L150-20, it should be pointed out that the special train service in question would be called “the Riveter.” Its mystique is related to the lack of photographic evidence of it, no mention of it in printed railway schedules, and no operational details from company-produced documents.

L150-40-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 96352cv, (Image 8 of 21)

From the onset of the creation of the “Riveter”, the financing agreement between the shipyard and railway was never formalized in a way to reflect the dependency of the actual ridership of the train.

L150-45-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38562, (Image 9 of 21)

This unresolved financial arrangement between the shipyard and railway became very apparent by the close of 1919 as the initial burst of shipbuilding activity became less dependable.

L150-50-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38562, (Image 10 of 21)

Following a worker strike and cessation of free SP service to Bay Point, D. C. Seagrave of the shipyard implored Harry Mitchell to pick up the slack to address the shipyard’s need to transport its workers.

L150-55-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38563, (Image 11 of 21)

Mitchell’s response to Seagrave pointed to the challenge of coordinating the Riveter’s stop at Saranap with the regular mainline train. Leaving out the specific operational issues, noting coordination with an east-bound mainline train as necessary suggests that the Riveter’s cars were attached to the mainline train at Saranap. The lack of interest to take passengers directly to the shipyard is also emphasized.

L150-60-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38563, (Image 12 of 21)

To address the coordination of trains at Saranap, a look at a 1920 schedule for the Sacramento-San Francisco Railroad, the new name for the bankrupt railway, will be presented next.

L150-65-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 13 of 21)

According to this schedule, the earliest east-bound mainline train did not reach Saranap until 8:15 AM. Nothing corresponding to the Riveter is noted.

L150-70-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, (Image 14 of 21)

While admiring the middle panel of the west view panorama circa 1918-1919 from L150-20, it is interesting to note the lack of detail of the operation of the Riveter and the continued lack of clear communication between the railway and the shipyard since the inauguration of service in early 1919.

L150-75-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 96358cv, (Image 15 of 21)

The shipyard was desperate enough to begin payments for the Riveter service in December 1919.

L150-80-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives 38563, (Image 16 of 21)

Years after the Riveter service had been terminated, a most illuminating exchange of letters transpired between Harry Mitchell and W. H. George in response to questions by the latter. Note in the last paragraph, right, the mention of Burgess’ Bridge, never used to deliver passengers to the shipyard proper, and, as far as we know, never adorned with overhead wire. See the next panel for more ...

L150-85-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38563, (Image 17 of 21)

A copy of the commute rates statement sent by Harry Mitchell to W. H. George of the Bay Point and Clayton Railroad with the letter of Apr. 16th, 1927. The fall in ridership doomed continued operation of the Riveter.

L150-90-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 38563, (Image 18 of 21)

The final most northerly panel of the west view panorama circa 1918-1919 from L150-20 shows how Maybeck orchestrated placement of various levels along three curving roads for the 120 homes completed. The homes were said to have been painted in a wide spectrum of colors.

L150-95-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 96359cv, (Image 19 of 21)

By circa 1929 when this image was taken, the population of Clyde was said to be reduced to near nothing as the shipyard focused on ship repairs, if anything at all. The hotel would burn down in 1969 after serving multiple alternative uses, but the homes remain today. Ref: API 563_6_BOX 59113

L150-100-George Russell Photo, California State Lands Commission , (Image 20 of 21)

For both Charles A. Smith and Robert N. Burgess, sustained financial success and operational longevity were not to be in on the North Coast. A neighbor to the east, however, did beat the odds, the Depression and even the incursion of the Navy in the 1940s, as will be reviewed in the next update of Industry of the North Coast. South view down the SN tracks at Clyde, undated.

L150-105-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 97697sn, (Image 21 of 21)