Part 1 – Redwood School No Longer in Session

L212-05-Herrington-Olson Photo, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 132236cv, (Image 1 of 44)

L212-10-Acknowledgements, (Image 2 of 44)

Understanding how eminent domain saved Lamorinda in the 20th century primarily flows from the evolution of the water delivery system and its impact on highway construction. The water portion is divided into three presentations in this part of the History section, while the highway part will be placed elsewhere.

L212-15-R.L. Copeland Photo, from the collection of the Moraga Historical Society, Moraga, CA, (Image 3 of 44)

This roadmap outlines the interdependence of the evolution of water delivery to road and railway creation, and ultimately the impact of population growth in Lamorinda. This update will focus on the acquisition of large tracts of land in central Contra Costa County, CCC, by private water companies to create reservoirs after WWI to supply bayside cities in the East Bay.

L212-20-Compiled by Stuart Swiedler, (Image 4 of 44)

Lamorinda in 2019 is superimposed on a 1980 map with Lafayette in black, Moraga in gold, and Orinda in violet, incorporated as cities in 1968, 1973 and 1985, respectively. Almost all the events to be presented occurred prior to incorporation of the cities, but these boundaries are important as the surrounding area today is almost entirely park land, recreation areas, reservoirs and watershed.

L212-25-1980 AAA Map Modfied by Stuart Swiedler, (Image 5 of 44)

The constitution does not define the limits of eminent domain, but instructs in the 5th Amendment that private land taken for public purpose may not be taken without just compensation. At the Federal level, the Supreme Court has typically supported eminent domain for a wide variety of situations since 1875. This “take” clause was extended to state and local governments when the 14th Amendment was ratified on July 28, 1868.

L212-30-Courtesy www.justice, (Image 6 of 44)

The Supreme Court’s ruling in the Kelo v. New London case was widely unpopular. Afterward, President George W. Bush issued an executive order to limit federal government takings, and almost all states have enacted legislation to limit similar cases. The land taken in New London was never developed and remains empty as of 2020. The details of the story are retold in the movie “The Pink House”.

L212-35-www.supremecourt.gov.opinions.04pdf, (Image 7 of 44)

“Robbing the poor to pay the rich” wrote Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in her Kelo case dissent. No less so is the circuitous route of the Northern State Parkway in New York. Inappropriate payments and political pressure by the rich in the 1920s explain its path, a legacy of NYC Parks Commissioner Robert Moses as explained on pages 300-301 in “The Power Broker” by Robert Caro.

L212-40-Courtesy Google Maps , (Image 8 of 44)

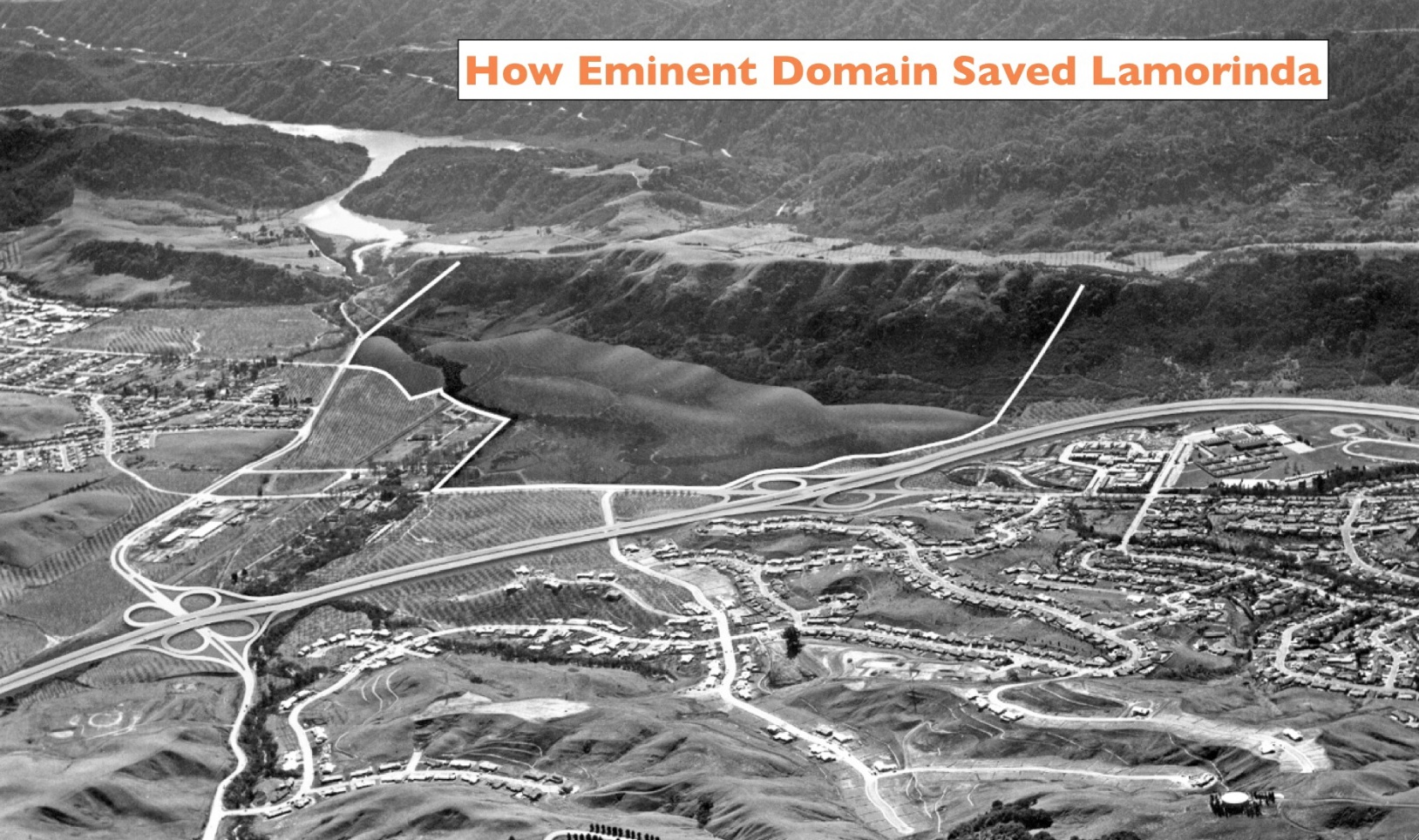

This east view from Apr. 24, 1967 of the BART tunnel west portal construction in Oakland’s Chabot Canyon brings in one additional point.

L212-45-Ed Brady-Aerospace Photo 11323, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 151537BART , (Image 9 of 44)

Many homes along Chabot Rd., shown in the upper photo from Apr. 4, 1953 were taken by the Federal government to facilitate building the tunnel. After the tunnel was completed, part of the excess land was sold at auction to the developer of the tennis club. The ultimate sale of excess land in cases of eminent domain played a significant role in Lamorinda.

L212-50-Copyright California Department of Transportation, 3301-18, Detail and Google Maps, (Image 10 of 44)

Finally, public utilities placement are not always the result of eminent domain. The intrusion of overhead electrical transmission towers such as this one seen in Lafayette in an east view from 2018 from the west terminus of Olympic Blvd. at Reliez Station Rd. is a good example.

L212-55-Stuart Swiedler Photo, (Image 11 of 44)

Turning the clock back 100 years ago indicates that the towers placed by The Great Western Power Co. did not involve a complex land acquisition. The electrical supply was desperately needed, and the land required was minimal in a relatively uninhabited area and available for sale.

L212-60- Courtesy John Harder, (Image 12 of 44)

The two major corridors of electrical towers through Lamorinda existed prior to significant population growth, the exception of the line indicated by the black arrow that was added after Briones Reservoir was constructed. Unfortunate for Orinda residents that the major substations within the purple rectangle are within today’s boundary of that city.

L212-65-Courtesy California Energy Commission Cartography Unit, (Image 13 of 44)

The Bay Area was in the sixth year of a horrible drought when this image was taken in Sept. 1923. Months before, voters from San Leandro to Richmond approved the Municipal Utility Act of 1921 to create the East Bay Municipal Utility District, EBMUD. In 1924, voters approved 39 million dollars in bonds to build Pardee dam and a 94-mile aqueduct from the Mokelumne River, the so-named Mokelumne Project.

L212-71-Eston Cheney Photo W-338, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 14 of 44)

Back to the map of 1980 with the city boundaries removed, indicating the positions of San Pablo, Upper San Leandro, Lafayette, and Briones Reservoirs, colored rectangles, prior to the date of city incorporation in Lamorinda. The story begins back in the first years of statehood as reviewed next.

L212-75-1980 AAA Map Modfied by Stuart Swiedler, (Image 15 of 44)

In 1858, the California Legislature approved the application of eminent domain to the acquisition of land by private water companies that would supply drinking water and fire-fighting needs to the local population. Many individuals took advantage of this opportunity to obtain land for which the water supply was fleeting, and, as can be expected, this land may have later served other purposes.

L212-80-Statutes of CA. Passed at the 9th Session of Legislature, Courtesy Google Books, (Image 16 of 44)

Marion Francis “Borax” Smith and Frank C. Havens formed the Realty Syndicate in 1895, and by 1903 expanded to approximately 10,000 acres of Alameda County not involved in water supply. That would change on Jan. 29, 1906 when they consolidated other private suppliers to form the Syndicate Water Co., delivering water to Piedmont and the Oakland hills. When they acquired the Contra Costa Water Co., CCWC, according to the June 11, 1906 New York Times, the name was changed on Aug. 30, 1906 to the Peoples Water Co., PWC.

L212-85-John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 17 of 44)

Muir Sorrick’s book ‘The History of Orinda’ states that PWC bought property in the area of the present San Pablo Dam, San Pablo Creek, and Bear Creek, including 442 acres owned by Richard Rowland in 1906. In addition, they received land from the Contra Costa Water Co., CCWC, acquired primarily from the Moses Hopkins Estate that included the Wagner Estate. Whether these acquisitions or the many shown on this map were by eminent domain or not has not been uncovered. Ref: G4363.C6 1908.M3

L212-90-Courtesy Earth Sciences Library, U. of California, Berkeley, (Image 18 of 44)

Relying too heavily on shrinking well water reserves, increasing debt, with implementation of water meters as their only innovation, PWC failed to deliver any water to central CCC, let alone keeping up with the cities along the bay, and was reorganized as the East Bay Water Co., EBWC, on Nov. 13, 1916. As John W. Noble explains in “Its “Name was M.U.D.”, embroiled in drought, the new company returned its focus to the bayside cities, and lobbied for new tax revenue to complete a new dam.

L212-95-Stuart Swiedler Photo , (Image 19 of 44)

A closer look at the 1908 map of CCC reveals where PWC had earlier lobbied unsuccessfully for creation of a reservoir along San Pablo Creek, orange arrows, along its significant land acquisitions on the creek’s periphery. Persistent drought allowed EBWC to complete the project in 1919. San Pablo Reservoir would only supply the bayside cities and not Lamorinda. Ref: Ref: G4363.C6 1908.M3

L212-100-Courtesy Earth Sciences Library, U. of California, (Image 20 of 44)

San Pablo Dam and Reservoir required 23.37 square miles of watershed, more than double that of Lake Chabot, with total reliance on creek and run-off from the surrounding hills. It was never completely filled under these circumstances.

L212-105-Eston Cheney Photo W-646, Herrington-Olsen Collection, Courtesy BAERA, WRM Archives, 132665, (Image 21 of 44)

Although deriving no water from it when in private hands, Lamorinda benefitted by this large mass of protected land bordering its southwest rim, limiting road construction save for San Pablo Dam Rd. and Bear Creek Rd. Ref. G4363 A3646 1920.L3

L212-110-Courtesy Earth Sciences and Map Library, University of California, Berkeley, (Image 22 of 44)

The bonds for EBMUD in 1924 limited activities to the Mokelumne Project, but water shortages were so serious that EBWC was permitted to create the Upper San Leandro Reservoir, equal in capacity to San Pablo Reservoir, but requiring over 30 square miles of watershed. Although only a tiny portion was located in CCC, the reservoir relied on the latter’s creek water. The county would never receive water from this reservoir.

L212-115-Courtesy news.google.com, (Image 23 of 44)

Even though San Leandro Creek supplied Lake Chabot, the 19th century builder and owner, CCWC, had not secured any land where the proposed reservoir was planned, left panel. PWC had obtained several properties by 1910, right panel, but it is not known if the latter applied eminent domain. Refs: G4363.A3.1900.A5.N.W., left; G4363_A3_1910_A5a, right

L212-120-Courtesy Earth Sciences and Map Library, University of California, Berkeley, (Image 24 of 44)

As described in the book “Moraga’s Pride”, the Community of Redwood or Kaiser Creek District was settled in the 1860s and 1870s by forty Portuguese and Yankee squatters who populated the “road to William Castro’s”, the Camino Pablo which ran from Moraga to Hayward. The dam would be located at the south end near Miller Canyon. An unattributed, but very informative hand drawn map of the key features of the Community of Redwood with important landmarks is shown here.

L212-125-From the collection of the Moraga Historical Society, Moraga, CA, (Image 25 of 44)

Few images of the homesteads in the area have been found.

L212-130-From the collection of the Moraga Historical Society, Moraga, CA, (Image 26 of 44)

In some cases, information about the properties are known, such as the saloon and home of resident Thomas Rees from this photo secured by Louis L. Stein. Most of the northern boundary hillside property belonged to ranchers who used the area for their cattle. The 1910 map in L212-120 provides some of those owners, although records beyond this have not been found.

L212-135-From the collection of the Moraga Historical Society, Moraga, CA, (Image 27 of 44)

St. Isabel’s Catholic Church served the community from 1878-1910, with no details uncovered about its closure prior to the announcement of reservoir construction.

L212-140-From the collection of the Moraga Historical Society, Moraga, CA, (Image 28 of 44)

Redwood school served the community until the reservoir construction, as well as those living in Grass Valley in Oakland. More on this subject coming up.

L212-145-From the collection of the Moraga Historical Society, Moraga, CA, (Image 29 of 44)

The Berkeley Dailey Gazette of March 10, 1924 described the beginning of preliminary work to clear the site for the 3M dollar reservoir by EBWC, with actual construction to commence after the rainy season with a 1926 completion date. The diversion dam and inlet portal of the diversion tunnel shown here from June 10, 1924 were to allow winter flood waters to be diverted downstream to Lake Chabot, if necessary.

L212-150-Eston Cheney Photo, Courtesy East Bay Municipal Utility District, P-TR-1340, (Image 30 of 44)

The earthen dam would be 185 feet high and 658 feet long at the crest, with a 6827 foot supply tunnel through the East Bay hills, and a sand-based filtration plant. As 1924 progressed, a puddle trench for the main dam was excavated, excavation of the main fill started, a control tower at the inlet of the supply tunnel erected, and a portion of the supply tunnel driven. Progress into June of 1925 is shown here to the east of the dam with the workers facilities, northeast view.

L212-155-Eston Cheney Photo W-758A, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 31 of 44)

The 500 acres of land to be flooded had begun to fill by mid-1925, north view. The open spillway and supply tunnel would be completed later that year, and the transmission conduits and filtration plant started, but not completed until 1926.

L212-160-Eston Cheney Photo W-759, John Bosko Collection, Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 32 of 44)

A south view from Nov. 17, 1925 of the dam near the south end of the reservoir with the scaffolding for a circular concrete regulation control tower.

L212-165-Eston Cheney Photo W-885, John Bosko Collection. Courtesy John Bosko, (Image 33 of 44)

Three views of Redwood School at its original site to follow. Through eminent domain, EBWC acquired the rest of the Kaiser Creek District, 1200 acres from 10 owners, and amid protests, eliminated all roads, but agreed to reconnect Redwood Rd. For reasons unknown, they neglected to buy the land of Redwood School that sat on a bar 50 feet above the floor of the canyon, connected to the abandoned section of Redwood Rd. by a bridge. Ref: Oak. Trib. Sept., 14, 1925 and Nov. 11, 1925.

L212-170-Eston Cheney Photo W832, Courtesy East Bay Municipal Utility District, (Image 34 of 44)

The school either had to remain in place or be moved intact as California law dictated that had to be maintained until the end of the school year, June 30, 1926, even if no pupils were left, but attendance for the past year was greater than 5 students. Nine children from Grass Valley in Oakland had attended in 1924-1925. Ref: Oak. Trib. Oct 26,1925.

L212-175-Eston Cheney Photo W833, Courtesy East Bay Municipal Utility District, , (Image 35 of 44)

As the bridge to the school had been washed out by 1926, EBWC agreed to move the school and pay rent at the former Wild Cat Inn site on Redwood Rd. located 0.5 miles closer to Oakland. A permanent two-acre school site was never purchased by EBWC as the school had been closed for the year, falling short of the 5 pupil per year rule. The school building was razed at the new site at the end of the school term. Ref: Oak. Trib. Jan. 28, 1926 and Feb. 8, 1926.

L212-180-Eston Cheney Photo W835, Courtesy East Bay Municipal Utility District, , (Image 36 of 44)

The Alameda County Surveyor, George Posey, determined a new route to reconnect Redwood Road, with funds to widen the road contributed by the county and EBWC. The change in the route can be seen across these three panels, as well as the site of Redwood School in the 21st century. Refs: Oak. Trib., Apr. 4, 1926; Hayward Review, Apr. 23, 1926. G4363.A3.1900.A5.NW, left; G4363.A3P2 1933 .A5, center

L212-185-Courtesy Earth Sciences and Map Library, University of California, Berkeley and Google Maps, (Image 37 of 44)

The reservoir took the appearance of a dragon, 6 miles in length, with arms extending 1.75 miles up Kaiser Creek, 1 mile up Kings Creek, and 2 miles up Redwood Creek. The Aug. 5th, 1929 Oakland Tribune noted that the reservoir was nearly dry, 20 feet below the outlet tunnel, when Sierra water arrived. More importantly, the almost entirely Alameda County-contained watershed completely prevented any road or home construction to the southeast section of Lamorinda. Ref: G4363 A3646 1920.L3

L212-190-Courtesy Earth Sciences and Map Library, University of California, Berkeley, (Image 38 of 44)

The impact of this watershed on Moraga has been profound, but some historical context is necessary to add. Once the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern Railway started passenger service in 1913, James Irvine and the Moraga Co. were eager to develop the Valle Vista subdivision up to the PWC watershed as shown in this drawing from July 1915.

L212-195-Courtesy of Contra Costa County Public Works, (Image 39 of 44)

A southwest view of Valle Vista as the East Bay Water Co. announced plans to build the Upper San Leandro Reservoir as reported in the Jan. 17, 1924 Berkeley Gazette. This image, purported to be from 1924, shows that even before this announcement, development of Valle Vista never took off for lack of a dependable water supply and its isolated position relative to other bayside cities.

L212-200-Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 75176sn , (Image 40 of 44)

Moraga’s growth remained unchanged by its reliance on local ground or creek water, despite the flow of Sierra water via Moraga Creek to the new reservoir. The size of Moraga was also limited by the expanding watershed limits placed on its borders with no homes to the southwest of Camino Pablo. West view, 1935.

L212-205-HJW Geospatial Inc, Pacific Aerial Surveys, Oakland CA, Courtesy East Bay Regional Park Dis, (Image 41 of 44)

As a boom was experienced in most of central CCC post-WW II, Moraga’s population had reached only 2000 and remained fairly unchanged as seen here in this 1950 east view over Upper San Leandro Reservoir. Why a few structures that dotted the south bank of the reservoir survived is not known, but housing along Camino Pablo remained restricted to the northeast side. The town now was receiving EBMUD water, but not from Upper San Leandro Reservoir.

L212-210-R.L. Copeland Photo, from the collection of the Moraga Historical Society, Moraga, CA, 12, (Image 42 of 44)

Although housing eventually extended closer to the reservoirs border on the south side of Camino Pablo, the view from the Lafayette Moraga Trail overlooking the green bridge still looks very much the same as it did in this southwest view from the SN right-of-way, Aug, 15, 1937.

L212-215-Charles Savage Photo, Courtesy BAERA, Western Railway Museum Archives, 77355sn, (Image 43 of 44)

To summarize, the acquisition of large tracts of land in CCC by private water companies allowed for the construction of two large reservoirs whose water supply depended on local sources within the county. Despite the location, the populous of Lamorinda did not receive any of this water, and this further isolated the region from the bayside cities of the East Bay.

L212-220-Compiled by Stuart Swiedler, (Image 44 of 44)